Helicopter Parents and Building of Resilience and Grit

Post written by Mary-Denese Holmes

I have heard, of late, the term “Helicopter Parents” being applied to parents engaged in the life work of growing-up the children and young people in their care.

At the outset I need to be clear that I include in the term ‘parents’ the many and various blends of couples, singles, extended families, fostering and services that do the parenting and caregiving work of growing-up children and young people.

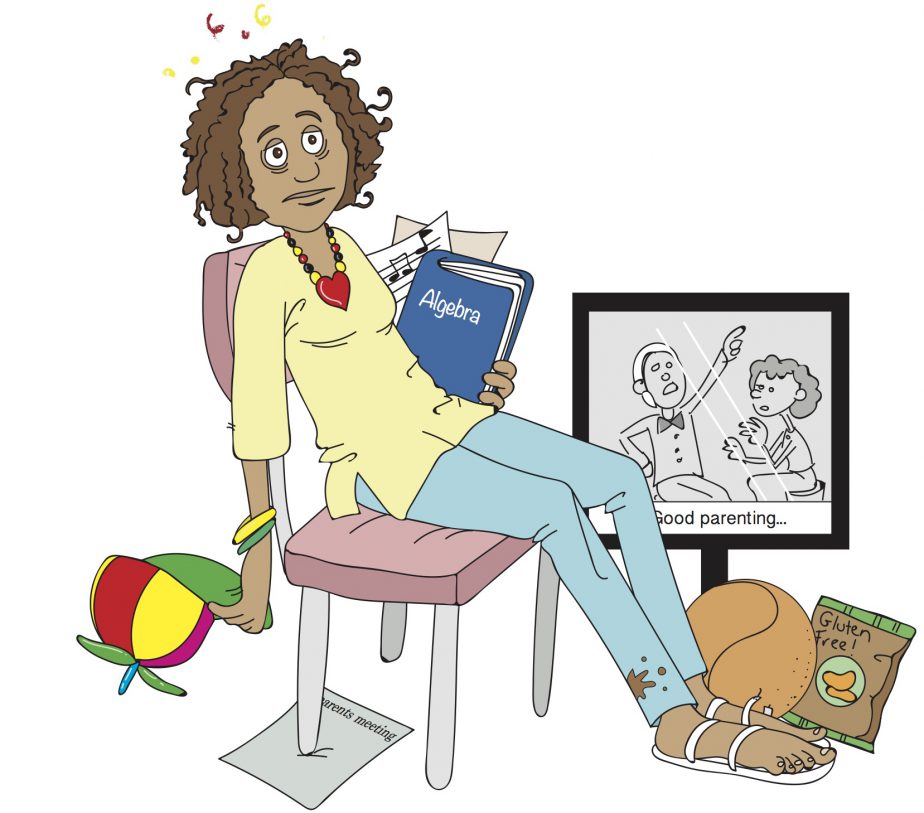

When I asked for understandings of the term ‘helicopter parents’ the language used to describe this sort of growing-up work was harsh, pejorative, totalizing, demeaning and ascribing of failure. I was invited to think about parents as people who hover and are never out of the picture, are over-protective and over involved, who mollycoddle, give-in-to, wrap in cotton wool, over- indulge, are slaves to and afraid of their children, are too weak to stand their ground, over-compensate, are over vigilant and never give their children breathing room. It is worth noting that many of these demeaning descriptors have a strong gender bias and are very often directed to the person doing the mothering role in this growing-up work.

My curiosity was alerted by these conclusions so I invited parents to share some conversations with me during which I asked them how they would talk about this growing-up work they do, what this commitment might stand for, what they might want appreciated about this life work they were engaged in and how they felt about the term ‘helicopter parent/s’ being applied to their caregiving.

I was careful to include in the conversations parents from seven countries and cultural groups, representing a range of ages and various spans of care-giving experience, who are currently growing-up children and young people in the age ranges of 1½ years to 18 years.

The care and concerns that parents spoke of about their growing-up work, their hours of reflecting on this work, the sharing of and testing out of ideas in their community, the carrying of and holding onto hope in the face of endless hurdles and doubts was humbling to hear. The parents yearning to have their children and young people grow into just and caring adults was stated time after time in these shared conversations. They talked of the sleepless nights spent worrying about the sadness and distress their children had spoken of when they were bullied, tormented and felt helpless in the face of tortures acted out on their lives. They spoke of their desire for a world where children and young people could be safe to live out their ordinary days and how yearning for that safety was mocked and derided as ‘helicoptering’. Parents spoke of school spaces where their children and young people experienced teachers committed to their well being and development as learners and how at other times this space was compromised by practices of derision and malice.

They spoke of the tricky and often demoralizing experience of listening to the judgements applied to them and their parenting work by various groups and individuals, often by people who had never taken on this sort of commitment and work. These frequent invitations to see themselves as failures and have their children judged as failures-by-association seriously undermined their holding on to hope and optimism for their children’s’ futures. They also spoke of how trying to meet or stand against society’s expectations, depending on how well the ideas fit for them, took them away from the joy of this growing-up endeavor.

Parents spoke about the recent years when they were exhorted to affirm, applaud, appreciate and pay great attention to every small achievement of their children/young people, lest they grow up damaged with low self-esteem and lacking in confidence, as being exhausting of them (and also of the children who ached for less attention). They felt themselves judged at every turn and were again found wanting in their growing-up work. Other parents who said they had tried to grow-up their child/children in a ‘robust way’ in this so called ‘caring’ climate were loudly criticized and seen as parenting in harsh, old-fashioned and strict ways in which they were described as uncaring parents.

The weather vane of public opinion has now veered in yet another direction, pointing firmly to the requirement of building ‘grit and resilience’ in children and young people. Parenting work is once again under the scrutiny of the public gaze and the verdict is ‘hovering and helicoptering’ is OUT, and the new IN is the requirement for children and young people to demonstrate an ability to struggle and BOUNCE in the face of life’s setbacks, to pass the test of showing grit and resilience against an ever changing set of criteria or they too will be deemed the failed product of helicopter parents.

The concept of Grit and Resilience and how these might look as practices in all our lives as well of those of children and young people holds enormous and exciting possibility. However the timing, degree and particularities of these concepts, the who, where, when, why, in what guise and how they might support a lived life require care-filled and nuanced appreciation. The adoption of these ideas without a negotiation of shared meanings and context, being used merely as a measurement tool of good or poor parenting seems counter productive to the growing-up work today’s parents are currently engaged with.

I have written previously on failure, and how it is the creative product of modern power at work in people’s lives. I am wondering if this current vogue of building grit and resilience and the invitation to watch and judge parenting work is a new site of failure to the growing-up work of parents. Is it another attempt by modern power to recruit parents into a sense of despair and self-criticism? Parents mentioned they are available to this new pressure because it speaks to their desire to have their children and young people feel good about themselves, to be able to participate in the world in a meaning filled way, to become adults who will contribute to creating a just and fair society and for a future where they will experience joy, love and connection. This trying to achieve the best outcomes for the children and young people in their care leaves parents available to harsh self-scrutiny. Failing to meet a new set of criteria they have had no say in negotiating, and which may have little to do with the values they bring to their parenting work seems to them a Sisyphean task.

The positing of a new vogue for parents to fail in seems hardly a useful and life affirming climate for the growing-up of our future world makers. The invitation for us all to mindlessly take up acts of parenting scrutiny offered under the guise of ‘caring for children’ and to add our voices to social media’s echo chamber to validate these ideas, without some analysis and discernment of where the ideas come from, seems to me to be a seductive but damaging opportunity.

I am left wondering what might become visible if we asked questions about who might benefit from this new site of parental failure, where these ideas have come from, what hoops it is requiring of parents to jump through, and what has happened in the past as new ideas about parenting have moved from exciting possibility to a site of parental personal and even moral failure. I’m curious about how much response-ability each of us has individually and as a society to step away from punitive judgment and to stand with and communally support this growing-up work parents are engaged with.